Top 5 Fallacies of AOL’s Vision for Patch

“To not believe in Patch, you have to believe that consumers in a town don’t want local information, they don’t want local advertising or commerce, and they don’t want a platform they can engage on.”

AOL CEO Tim Armstrong, For AOL, a Costly Gamble On Local News Draws Trouble, WSJ

I don’t know whether Tim Armstrong’s statement above is spin or his actual vision about Patch. In either case, it’s rare that somebody can fit so many fallacies in one sentence.

1. The Fallacy of Faith

“To not believe in Patch, you have to believe …”

This is about belief? Really? Words like “belief” should be restricted to discussions about religion, values, and people. When a businessman uses those words to predict the success of a business model, run for the hills.

A business model is no place for language about heretics and believers. If that’s the mindset you’re applying to your business strategy, you’re likely to keep doubling down with unjustified large bets on models that are failing.

2. The Friendster Fallacy

Would you say that to not believe in Friendster (or MySpace) is to not believe that people want to share information with their friends? To not believe in Patch may be to simply to suspect that AOL’s entry will the Friendster to another company’s Facebook. Maybe a startup. Or Google or Facebook. Or some other existing business that expands their offerings. Who knows? My money would not be on AOL.

3. The Illusion of the Market Vacuum

Sure I want sources of local info. Sure I want a platform to engage on. And I have them. Lots of them.

There are online and offline local newspapers. Geo-targeted ads follow me whether I want them to or not. I use existing social networks and commenting features to engage others.

The WSJ says that Armstrong started Patch because he was “frustrated by the lack of local online news about his hometown of Greenwich, Conn.” OK. The Greenwich Post and the Greenwich Citizen are trying to solve the same problem. So are countless bloggers. So are bigger news sites. This is the web. Big news (and social and commerce) sites can (and do) throw in local content and advertising targeted to each user.

There may be an opportunity here for a dedicated solution. But more likely existing players will expand to fill the vacuum.

4. The 1% of China Fallacy

Skipping ahead in the column, the WSJ mentions

The idea was to target wealthy small communities that generated about $20 million a year in advertising though TV, radio, newspaper and direct marketing.

They quote Jon Brod, who worked with Armstrong to develop the model

“We basically said, ‘based on our model, if we could get [less than 1%] of that $20 million, we would have a profitable Patch in that community,” Mr. Brod said.

One of the earliest business models I heard started with “if we could get just one percent of Chinese consumers …” If you’re looking at one percent of a large market, then you haven’t segmented your market enough to be making hundred million dollar bets. You should be confident about a larger share of a smaller segment before investing that much. For example, we’re aiming for 20% of the $1 million spent by local restaurants in direct advertising campaigns. And we’re confident we can get it because we’ll be attracting exactly the user base that these restaurants are failing to reach through other methods. Spending over a hundred million a year with such a nebulous view of your market segment, what they want, and why they’ll choose you? Ouch.

5. The Start Big Fallacy

The columnist asserted that you had to start big on a play like this. Why? This was the perfect area to start small.

Yes, there’s an issue of achieving critical mass in a location. Fine. But couldn’t they have started with small bets in one or two locations? The WSJ says they’re losing an average of over $100,000 per town per year. Which wouldn’t be terrible if they were getting the kinks out before going big. But they’re operating 850 sites for a total loss of over $100 million per year. That’s $40 – $50 million in revenue with $160 million in costs.

The WSJ’s numbers are presumably somewhat misleading. They recently expanded from 30 towns to 850. Presumably most of that expansion did not involve an increase in personnel, and involved either splitting areas into smaller ones or expansion into neighboring towns. So perhaps the more accurate number is 30 metropolitan areas losing an average of over $3 million per year. However you slice it, they’re losing over $100 million a year.

Facebook started at Harvard. With a small budget. They tweaked. They grew slowly. They may not know how to run an IPO, but they know how to start a business.

Some Numbers

The WSJ writes

“The good news for Patch is that its traffic has grown sharply, swelling to 10.3 million visitors in April from 6.9 million a year earlier, according to comScore. Patch attributes the improvement largely to growth at its established sites.”

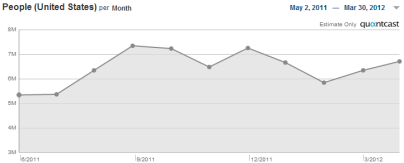

Well. Here’s Quantcast:

Patch isn’t quantified with Quantcast, so their numbers are probably too low, and they only go back to June. I’m willing to accept Patch’s claim to have grown from 7 million to over 10 million in a year. But Quantcast indicates that they peaked last fall.

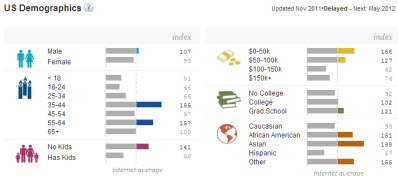

The demographics that Quantcast shows are also interesting. It claims that Patch somehow hit the most unattractive demographics: low-earning adults without kids.

Unlike eHow, Patch is news-oriented, so they’re unlikely to monetize well through Google AdSense. Also unlike eHow, their content is mostly oriented around transient, rather than evergreen, content. Therefore their investment is content is generally an expense that must pay off quickly, not an expenditure that will earn revenue for years.

Unlike leading news sites, they don’t have the quality or prestige to bring in high-end brand advertising.

They can target people in specific locations, but advertisers can get that same functionality from ad networks.

Summary

AOL hasn’t done much to earn the benefit of the doubt in their decisions this millennium. Patch might succeed. I’d bet not.

Said slightly differently:

- They “believed” in their model and portrayed the skeptics as heretics. I’d say this was the original sin that led to the others.

- They took the leap from “customers want these things” to “therefore our solution will bring in hundreds of millions of dollars in annual revenue.” That’s a large leap of faith.

- They ignored the possibility that they were wrong about the existence of a market opportunity.

- They ignored the possibility that even if they were right about the opportunity, a different player could seize the market.

- They failed to specifically define a market segment of which they would take a large slice. They were satisfied with the extremely vague one percent of a big market.

- They placed huge bets on unproven solutions and ignored evidence that they were failing. They could have started small, gathered data, rapidly iterated, and followed the data to determine next steps.

That’s without even discussing the cultural and management issues involved in their failure to merge the management teams of Patch and Huffington Post.

On the bright side, they provided some nice lessons in how not to run a business unit.